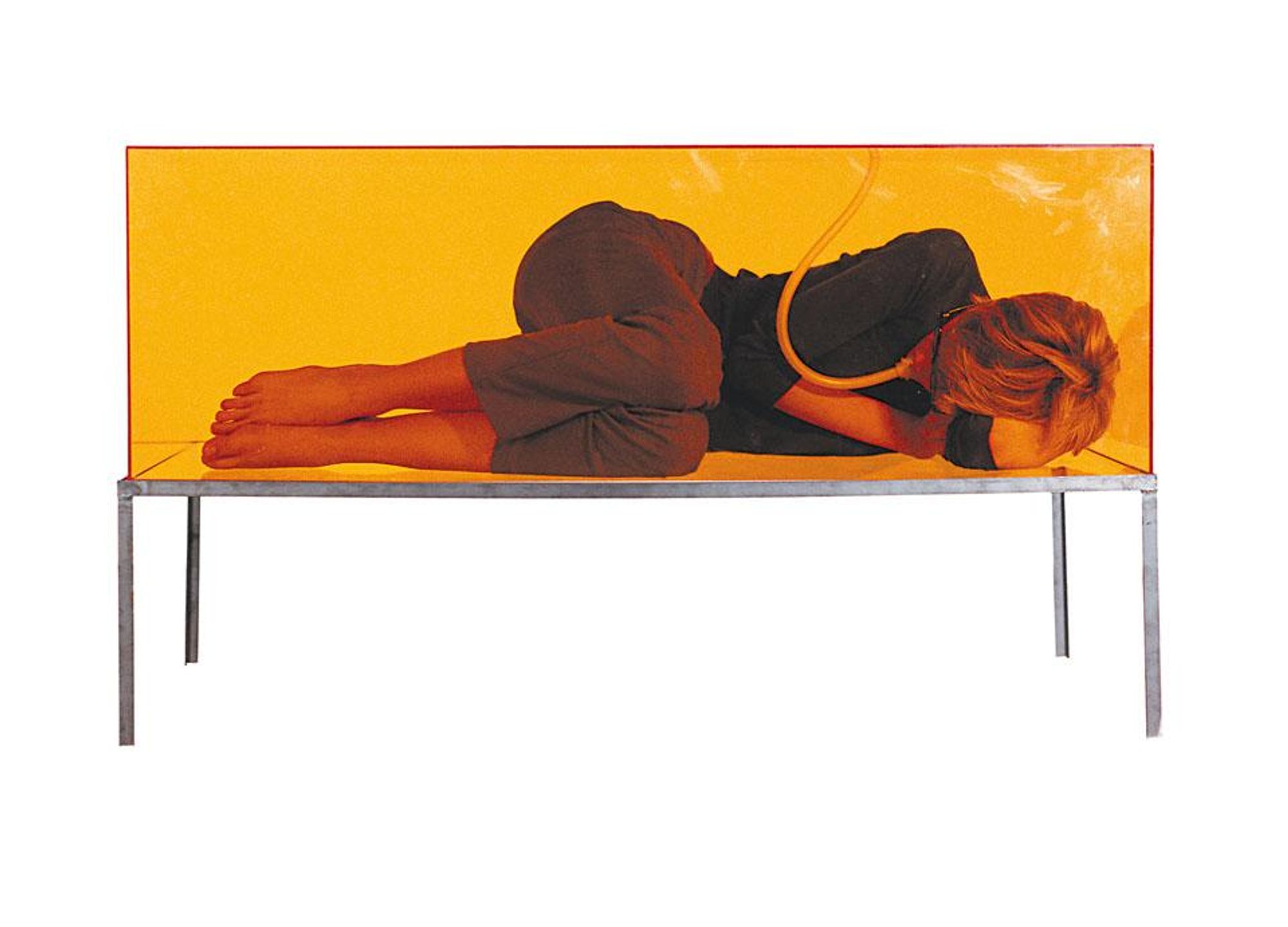

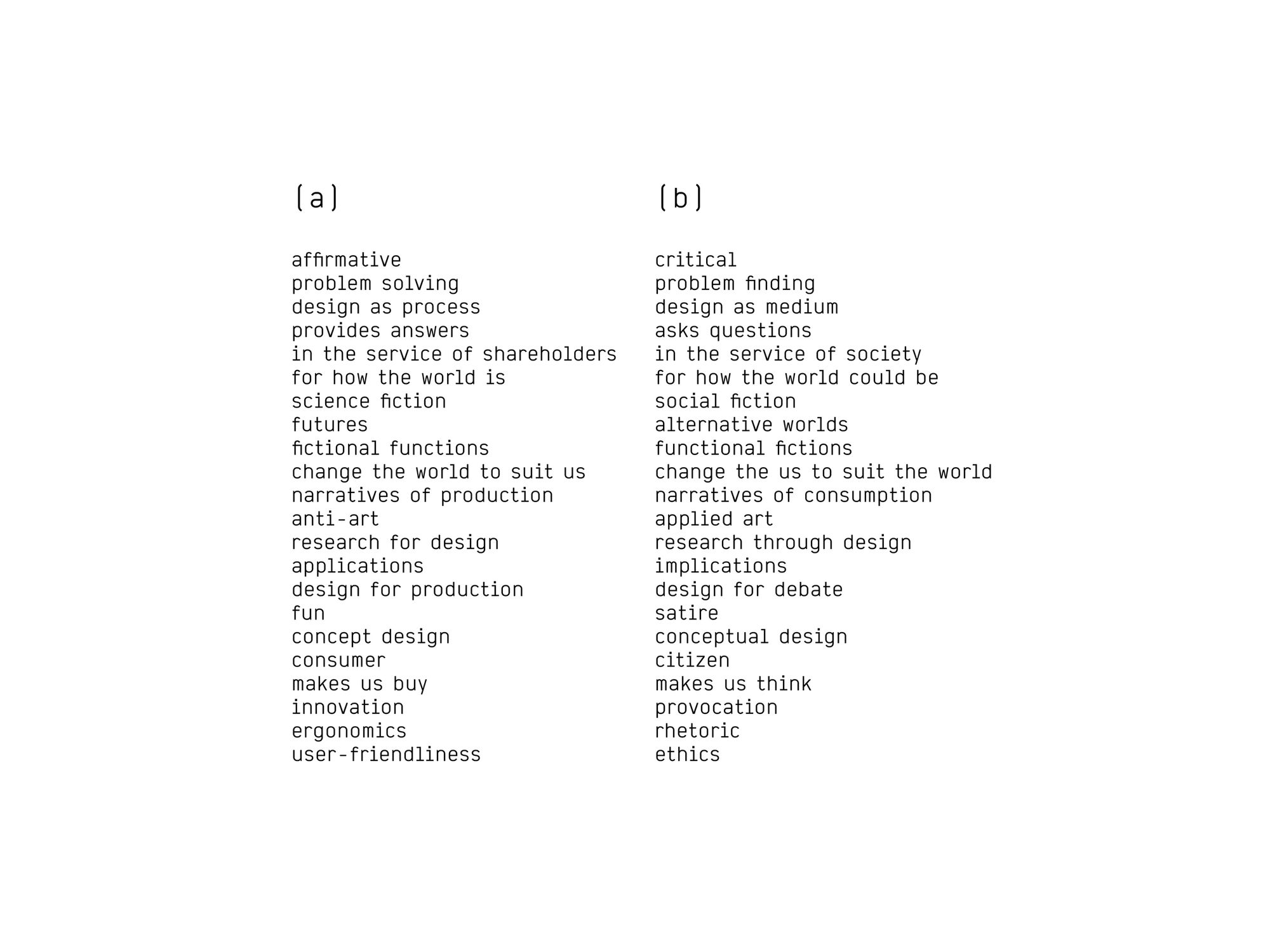

At the Royal College of Arts in London, the Computer Related Design (CRD) studio “set out an agenda for product and interaction design, positioning it as a vehicle for critical reflection on the role design and technology in society.”[i] Based on these interests, a “critical design” unit was set up within the CRD studio and led by research fellows Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. It’s fascinating that the term critical design was coined in the late 1990s, which situates it directly within the new paradigms of designing with, through, for, and about computation as a general-purpose technology—including all the unintended possible outcomes. Dunne first used the term in his book Hertzian Tales (1999), and Dunne and Raby further developed the definition of it in their book Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects (2001). Writing later on this topic, Dunne and Raby state: “Design that asks carefully crafted questions and makes us think, is just as important as design that solves problems or finds answers. … [L]et’s call it critical design, that questions the cultural, social, and ethical implications of emerging technologies. A form of design that can help us to define the most desirable futures and avoid the least desirable.”[ii]

Through their teaching, research, and practice, Dunne and Raby have come to be recognized as potent progenitors of a wave of critical design practices to follow, eventually giving form (and a name) to speculative design. According to Dunne and Raby: “Critical Design uses speculative design proposals to challenge narrow assumptions, preconceptions and givens about the role products play in everyday life.”[iii]

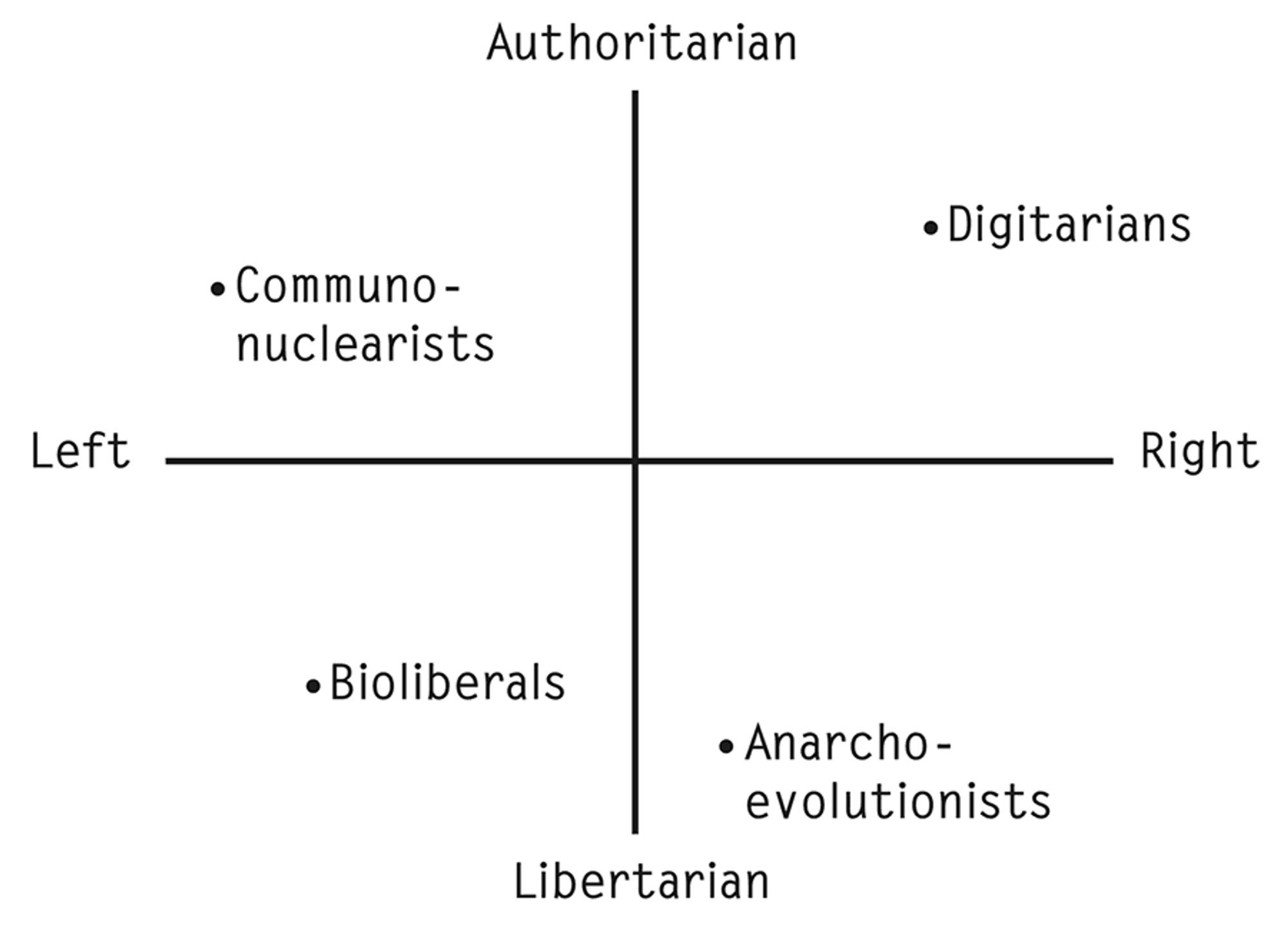

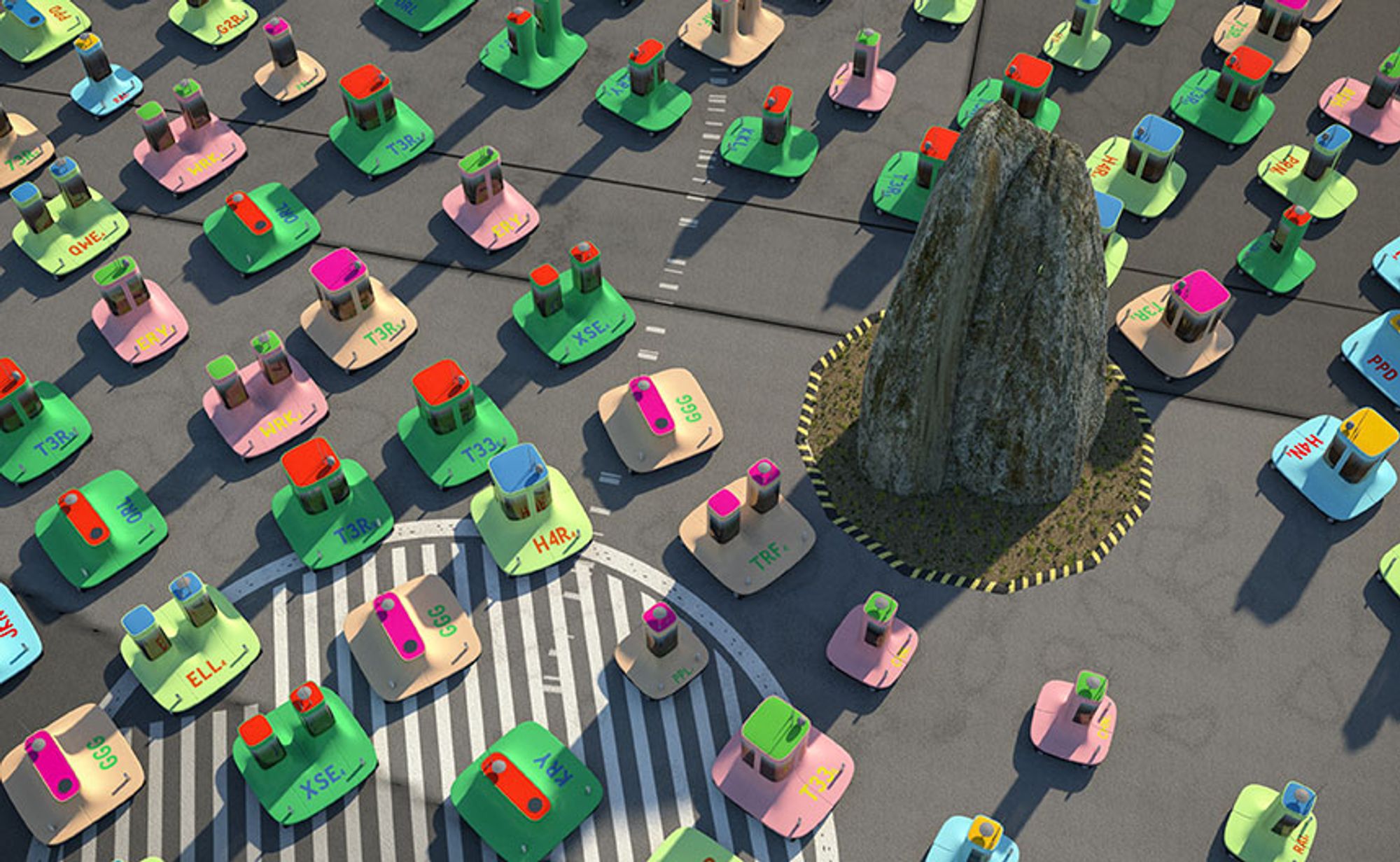

Matt Malpass further distinguishes speculative design by its specific focus “on science and technology, establishing and projecting scenarios of use; it makes visible what is emerging.”[iv] The genesis of speculative design within the larger discourse of critical design combined a desire to “find ways of operating outside the tight constraints of servicing industry,”[v] a new intellectual project for design, and a response to the perceived lack of criticality when design engages with new and emerging technologies. While not necessarily anticapitalist, the resulting inquiries through research and design indicate the limitations placed on market-driven technological innovation, suggesting that socially beneficial technologies require a different ideological orientation. For this reason, speculative critical design—a mash-up term that indicates the intersection of speculation and critique—is quite often noncapitalist in its pursuit of posing “alternative” scenarios of everyday life through designed objects and experiences.

[i] Malpass, Critical Design in Context, 30.

[ii] Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, “Towards a Critical Design,” Dunne & Raby, accessed June 16, 2021, http://dunneandraby.co.uk/content/bydandr/42/0.

[iii] Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, “Critical Design FAQ,” Dunne and Raby, accessed April 14, 2019, http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/bydandr/13/0.

[iv] Malpass, “Between Wit and Reason.”

[v] Dunne and Raby, Design Noir, 59.

👉 Home