Practically the moment industrial capitalism began, it was met with resistance. The Industrial Revolution brought radical economic and social change to England and shortly thereafter to much of the rest of the world. As factories spewed toxic pollutants into the world and workers were subject to alienating, dangerous, and endless work while living in poverty, owners became wealthy and set rules for the social and political institutions that would protect their interests. As a response to the expanding hegemony of the capitalist system, socialism emerged as an alternative. Socialists emphasized public (rather than private) ownership of means of production and social organization built on cooperation (rather than competition). Early nineteenth-century socialists such as the Welsh textile manufacturer Robert Owen and the French philosopher Charles Fourier argued for a system of social and economic organization based on small collective communities rather than on a market or centralized state. Karl Marx undoubtedly influenced socialist theory and helped make its ideas widely known. In particular, Marx’s conception of society as being produced through the dynamics of different social classes struggling for power has generated new ideas, new identities, and in some cases, new political realities.

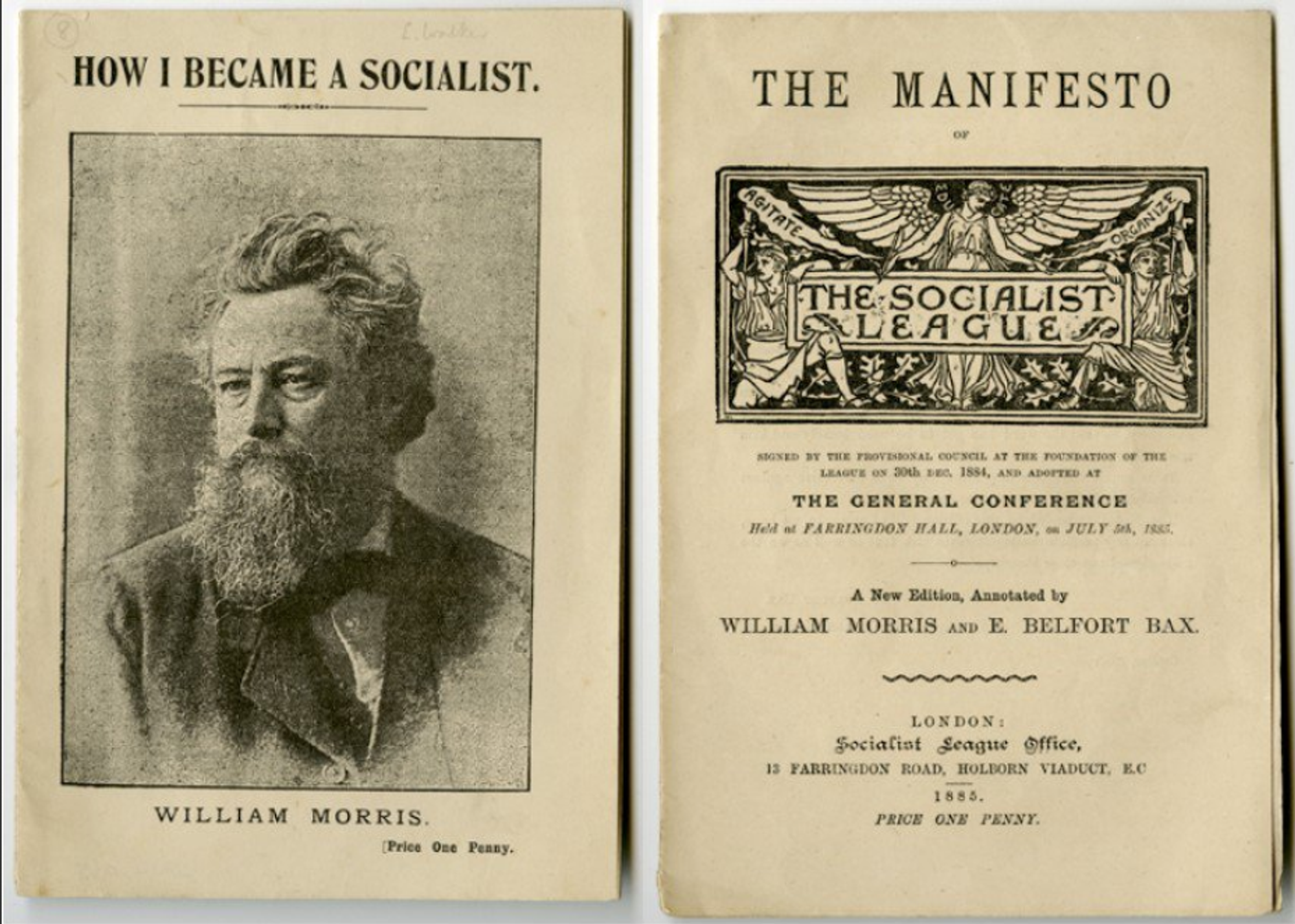

Perhaps the most familiar anticapitalist episode from design history is that of the British Arts and Crafts movement. Nominally led by William Morris, these nineteenth-century designers rejected what they saw as the destructive effects on nature, beauty, and human well-being by the use of machines for production of the objects of everyday life. The Arts and Crafts movement led a return to the traditions of craft and small-scale production, citing a kind of spirituality that connected humans to the act of making. Arts and Crafts designers created books, furniture, textiles, lamps, and many other home objects through laborious processes such as hand-stamping wallpaper and block-printing books. William Morris’s Kelmscott Press followed this logic of glorified labor to design and produce highly ornate, limited editions of medieval texts, such as the works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Politics was at the front and center of this movement. Morris was active in various organized socialist activities in England, working in opposition to the economic inequality and degradation of the human condition brought about by industrial capitalism. Describing his position, Morris said, “What I mean by Socialism is a condition of society in which there should be neither rich nor poor, neither master nor master’s man, neither idle nor overworked, neither brain-sick brain workers nor heart-sick hand workers.”[i] However, “while Morris’s ideology was opposed to industrial capitalism … he could not account for or effectively fight the increasing attraction of consumption (and shopping) across all classes of modern society.”[ii]

[i] Quoted in Raizman, History of Modern Design, 85.

[ii] Raizman, History of Modern Design, 85.

👉 Home