The long history of racial oppression in the United States met with the struggle for political representation and power in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In 1966, two young men studying at Merritt College—a community college in Oakland, California—cofounded a revolutionary socialist political organization that they called the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale based the intellectual orientation of the organization on a Marxist perspective that saw the American black community as a colony that was being perpetually exploited by white businessmen, the police, and the US government. Their political focus on class struggle and solidarity led them to build alliances with other radical groups across racial divisions—radical whites and Chicanos in the United States—and with revolutionary groups around the world. The Black Panther Party was founded on a 10-point program that “addressed the major issues facing urban black communities with demands for full employment and adequate housing.”[i] The final demand summarized the party’s objectives: “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and .”[ii]

Economic injustice was central to the Black Panther Party’s mission. The Panthers clearly recognized that even as legal forms of racial discrimination were beginning to fade, the economic oppression of black communities would keep them in bondage. Point three of the Party’s plan initially read: “We want an end to the robbery by the white men of our Black Community.” This was later changed to “We want an end to the robbery by the capitalists of our black and oppressed communities.”

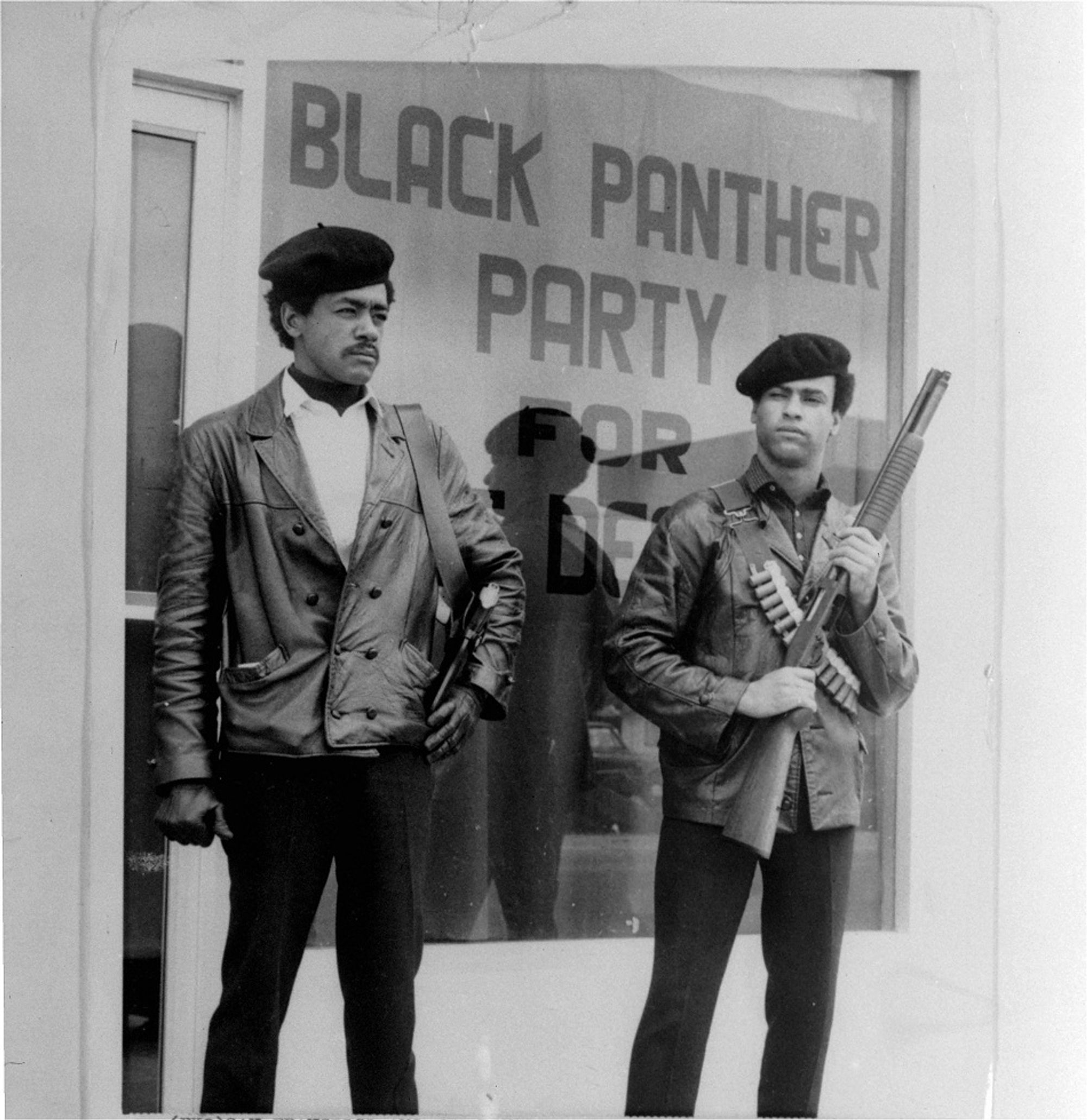

The Black Panther Party’s activities consisted of two main programs. One was community defense through armed patrols that monitored the police in black communities. They wore immediately identifiable uniforms on these patrols, leather jackets and berets that represented military discipline while also creating a new identity for black power. The second was directed at community service, particularly in making black communities self-sufficient. By 1969, the Black Panthers were serving free breakfasts to 20,000 school-age children in 19 cities around the country every school day. They also operated medical clinics and after-school programs, creating community economies outside the limits and control of a racist capitalist system.

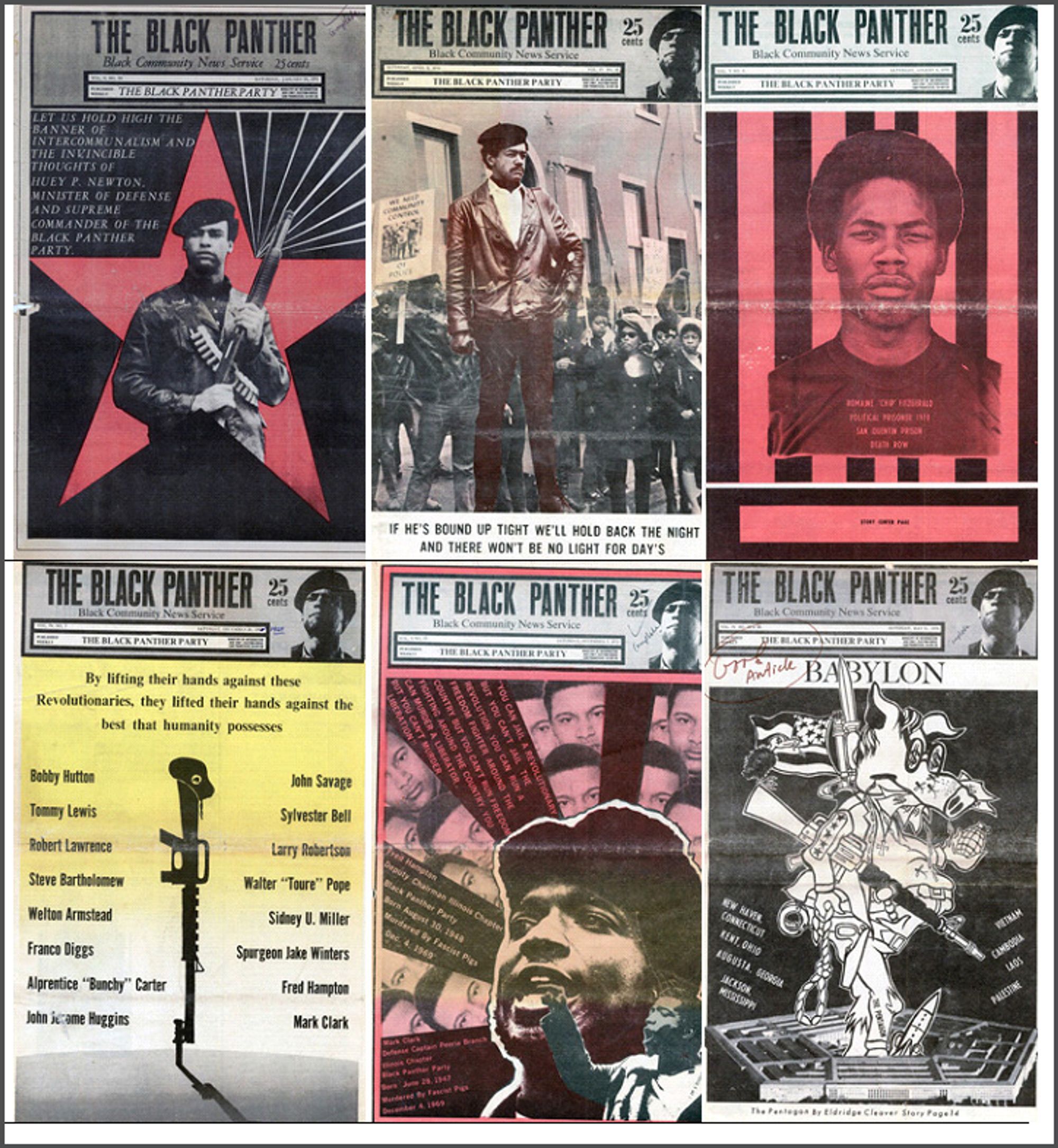

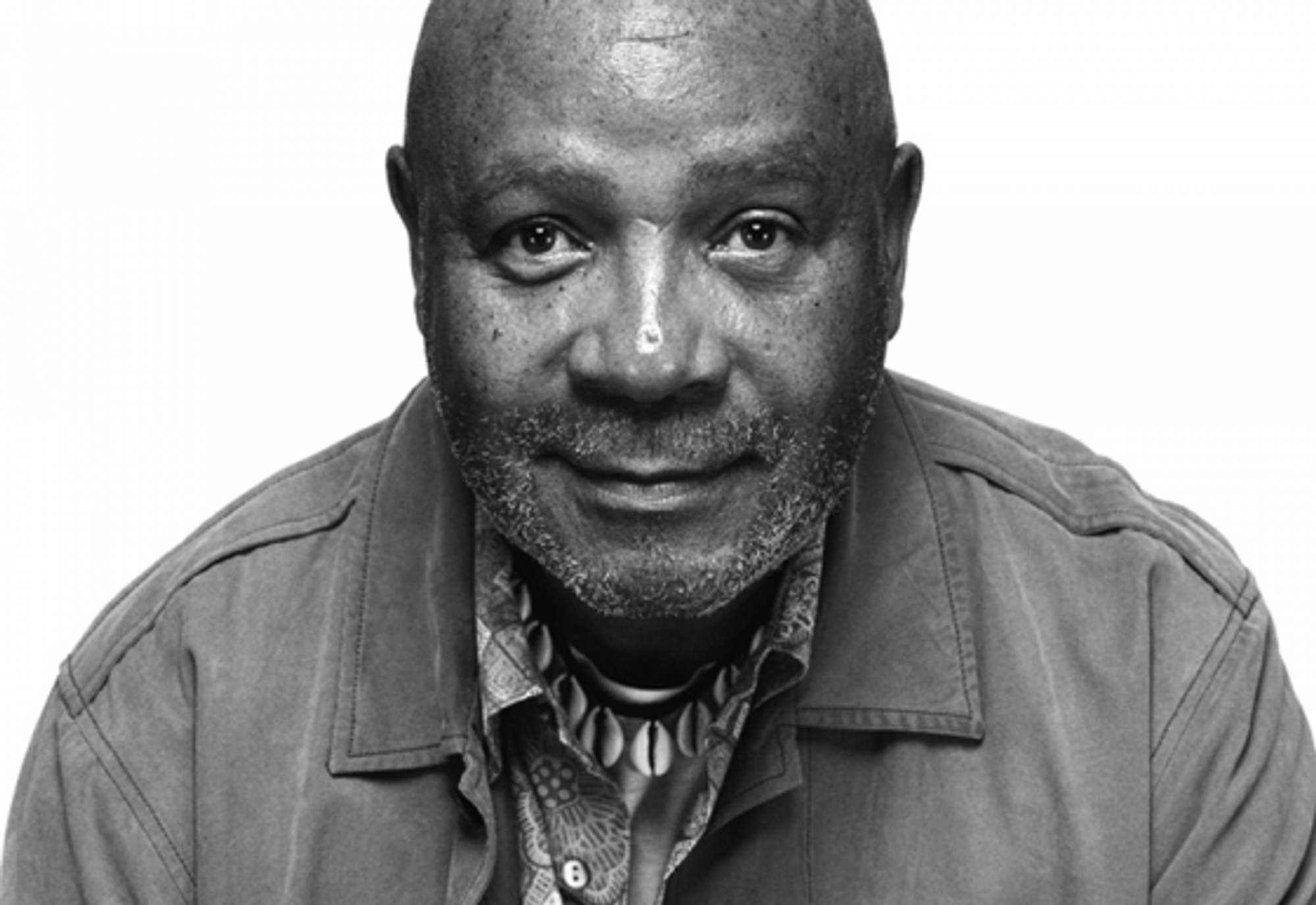

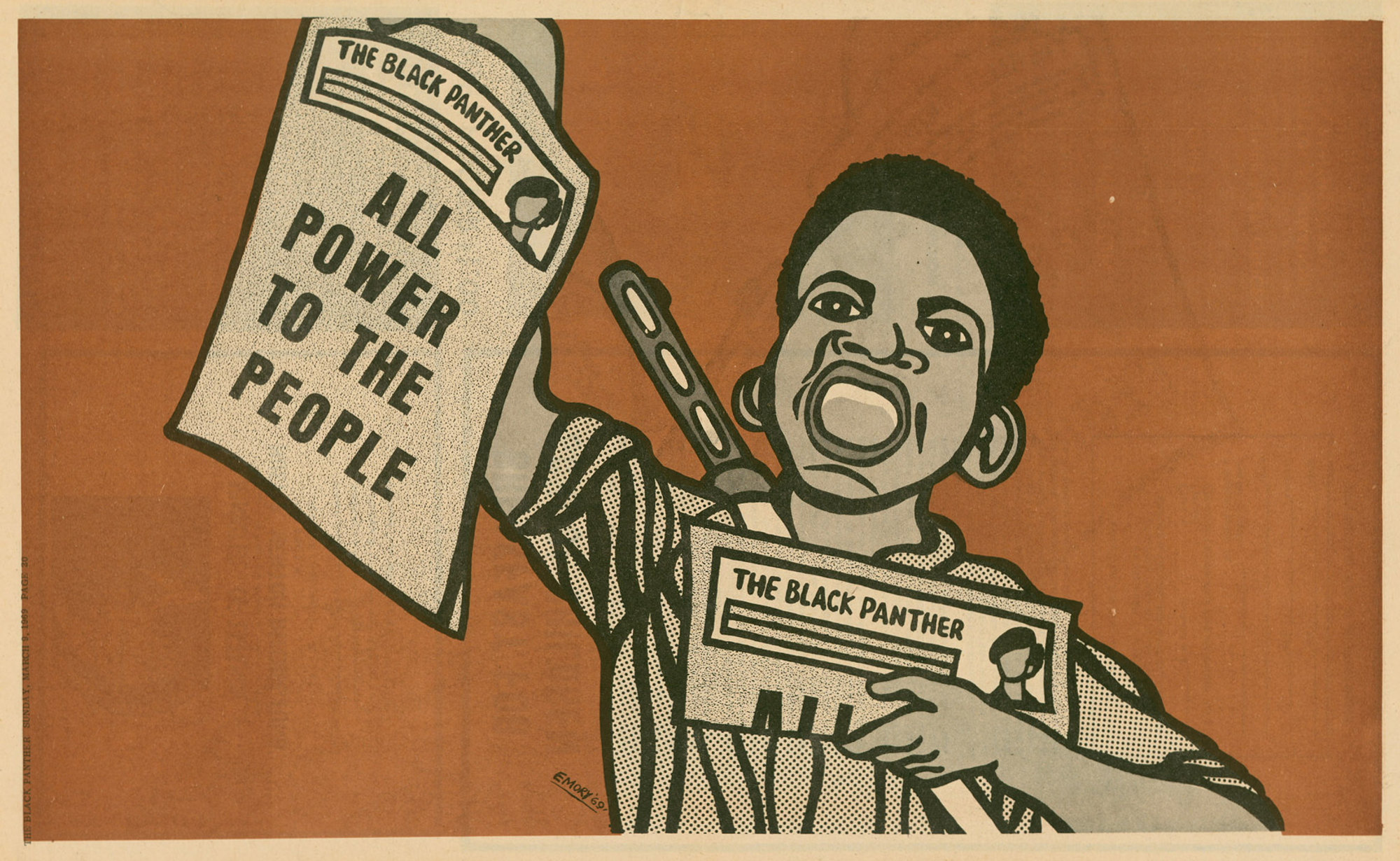

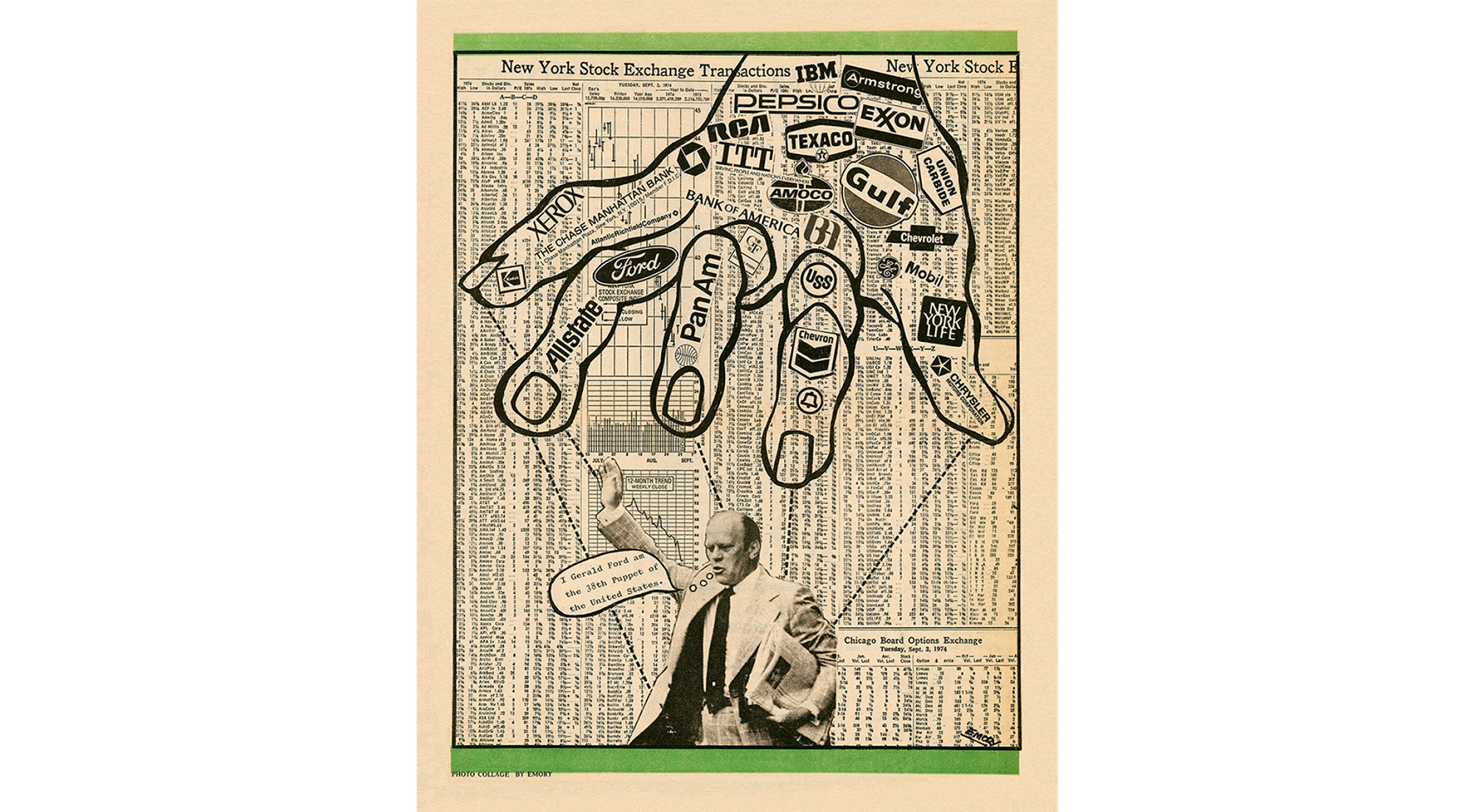

The Panthers needed to communicate with black communities in America and radical groups globally to maintain a flow of information on political and social events, build support for the party’s activities, and encourage participation in their programs. The party’s official news channel began on April 25, 1967, with the first issue of what was initially a four-page newsletter. During a meeting at the apartment of activist Eldridge Cleaver where Bobby Seale was working on the inaugural issue, party member Emory Douglas offered to help. Douglas had taken graphic design classes at San Francisco City College and had access to the print shop there. He redesigned The Black Panther and began to produce it on a web press, which gave him the opportunity to print color images. The front and back covers were used for dynamic graphic images and collages that aligned with the party’s messaging. A new issue’s front and back covers were also designed to operate almost like posters with imagery that could be readily identified and understood in black communities. Douglas “realized The Black Panther needed potent images to cut through the high illiteracy rates in poor communities.” From 1968 to 1971, The Black Panther became the most widely read black periodical in the United States and was distributed internationally, with weekly circulation reaching 400,000 copies. It continued publication until 1979.[iii]

Emory Douglas was the art director, designer, and main illustrator for The Black Panther, and he also served as the “revolutionary artist” and minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. In addition to the newspaper, he designed posters and other printed matter for recruitment and to spread the Black Panther ideology to oppressed and militant groups, using imagery to build solidarity: images of bloodied pigs (a dig at the police), “people in stances of active armed resistance, men draped in bandoliers, women holding infants and toting rifles.” Through these images, Douglas “branded the militant-chic Panther image decades before the concept became commonplace. He used the newspaper’s popularity … to incite the disenfranchised to action, portraying the poor with genuine empathy, not as victims but as outraged, unapologetic and ready for a fight.”[iv]

Through the newspaper, posters, and other printed materials, Douglas generated and circulated hundreds of illustrations, collages, and other designed images that chronicled the Panthers’ programs and struggles and created new subjectivities for the black power movement globally. Meanwhile, the newspaper operated to unify otherwise embattled and (quite literally) segregated communities around the world through a medium of visual communication, steeped in the political motivations of a community imagining and fighting for its liberation.

[i] Craig Collisson, “Black Panther Party (U.S.A.),” Black Past, January 28, 2008, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-party/.

[ii] Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation, “The Black Panther Party Ten-Point Program,” https://hueypnewtonfoundation.org/advocacy

[iii] Jessica Werner Zack, “The Black Panthers Advocated Armed Struggle. Emory Douglas’ Weapon of Choice? The Pen,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 28, 2007, https://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/The-Black-Panthers-advocated-armed-struggle-2568057.php.

[iv] Zack, “The Black Panthers.”

👉 Home